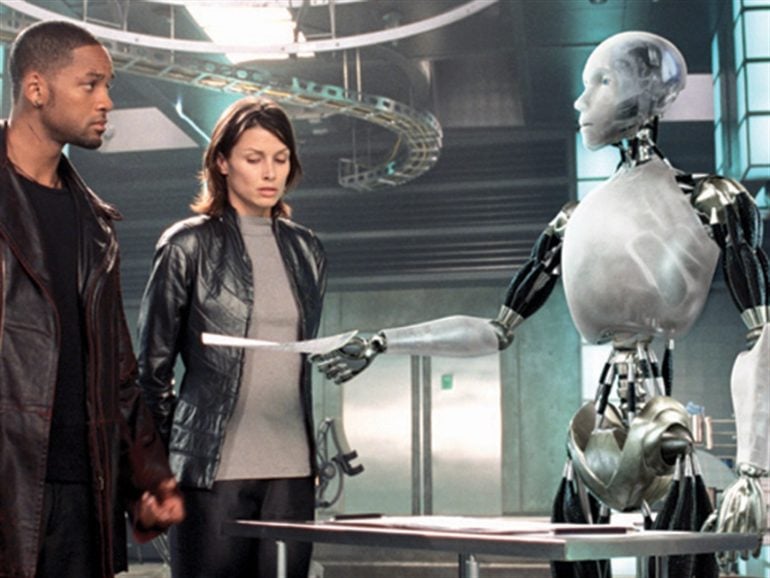

In 2030, the adjudicators of the World Trade Organization (WTO) are sitting in the Geneva headquarters to hear a trade dispute between the Republic of Robata and the Federal Republic of Daemon.

Robota, a developed country, is a superpower in artificial intelligence (AI) and takes the lead in designing and manufacturing vehicles equipped with fully automated driving systems (AVS)—otherwise known as self-driving cars.

Based on the business strategic calculation, major manufacturers in Robata tend to shape their AVS in a way that can reduce the legal risks to the minimum for the companies. In particular, the leading manufacturer, AutoVoi, has announced that its ‘Type X’ will be the ultimate answer to the controversial ‘trolley problem’—in the event of unavoidable accidents that raise genuine dilemmas (for instance, hitting a teenager or an elderly person, or a cyclist with a helmet or one without).

Not long after ‘Type X’ was first introduced into Daemon, a developing country, the hidden age bias was quickly uncovered by social media. Amid the public outcry, Daemon’s Department of Transportation and Department of Foreign Trade, having consulted a number of stakeholders, determined to provisionally ban the importation of ‘Type X’ and similar models until manufacturers remove what they consider ‘unethical’ algorithms from the systems.

In response, the Robata government called upon ‘Lex Cyborg’, a multi-talented robot lawyer, to prepare for this legal battle involving the complicated design of AVS, as the WTO dispute settlement mechanism also taps into the potential of ‘smart court’ due to budget constraints.

While this scenario might seem futuristic, advances in AI bring with it unprecedented challenges in scale and complexity to the current global trading system.

The rapid speed of technological development and advancement has left policy-makers woefully underprepared for the pluralist model of governance necessary for responding to challenges of global trade in the age of AI.

Before we can tackle these challenges, however, we must understand what ‘AI’ is.

There is no universally agreed definition of AI, though this term is generally understood as a concept generic enough to encompass a broad range of technology. It has grown increasingly common for policy-makers to classify the ‘intelligence’ of AI into ‘narrow (weak AI)’ and ‘general AI’ contingent on the scope of tasks undertaken.

For instance, the rise of ‘Automated Legal Advice Tools’ (ALATs), known as ‘Robo Lawyers’, exemplifies a broader tension of classifying AI within the traditional WTO goods-services dichotomy. This stems from current agreements being largely agnostic to the possibility of trade mediums holding personhood. Moreover, ALATs could reshape the landscape of the legal service sector by unbundling transactions into smaller tasks.

In turn, this could change the way ‘legal services’ can be offered and provided by whom in different jurisdictions, thereby casting doubt on how these new business models can squarely fit into the existing commitments under the global trading system or even the new generation of free trade agreements.

Another challenge comes in the form of the classic ‘trolley problem’. AI poses several complex ethical questions dealing with how these technologies are designed and applied in a manner consistent with human rights, as well as the public interests and the moral integrity of society.

The variance in global responses to the ‘trolley problem’ indicates public moral diversity exists alongside national and cultural boundaries. The challenge then lies in negotiating a holistic governance model capable of incorporating differences in ethical perspectives.

Yet another challenge can be seen in the AI ownership of algorithmic intellectual property rights. This issue relates to the core personhood of AI, in describing where the line of AI authorship is drawn.

In the UK, AI-assisted outputs are granted copyright protection under its Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988 (CDPA), although AI itself cannot be the author. Conversely, this approach is not necessarily shared by others—even within the common law world, like the US and Australia. These differences indicate the difficulty with transplanting an overarching framework across these systems.

IP issues are not confined to the authorship or inventorship of AI. Today, it is common to see governments incorporate AI in their decision-making process.

While AI seems a promising and cost-effective tool in governing public affairs, the concern over the explainability and transparency of the underlying algorithms and datasets—the so-called ‘black box’ problem – has been on the rise. Anyone who is affected by the government measures that involve an automated decision-making process—including foreign businesses—may find it difficult to challenge them.

For one, the rationales of how these algorithms and data operate can be problematic for humans to interpret—the so-called ‘technical black box’ issue. Moreover, as these tools are often protected by proprietary technologies in the form of trade secrets or patents, it is problematic to unpack the ‘legal black box’. It could be therefore a daunting task to see how countries reconcile the competing interests in this context without undermining the commitments under the existing TRIPs/WTO regime.

These examples illustrate the emerging challenges posed by AI and lead us to reflect upon the resilience necessary for dealing with the coming age. At the core of these challenges lies the differences in the economic, social and political underpinnings of governments.

Broadly, there are three possible ways that the global trading system can ensure an appropriate regulatory response to trade troubles of AI:

- Firstly, the need for institutional flexibility within the WTO to allow for rigorous and dynamic cross-sectoral dialogue and cooperation on AI-related trade issues. The focus should then fall on the adaptability, consistency, and optimal design of any proposed rule.

- Secondly, the global trading system should be more deferential to local values and cultural contexts in addressing AI-related issues. There should be greater caution and refrain from pushing strong harmonisation initiatives.

- Thirdly, the global trading system should accommodate and encourage emerging sites of governance concerning AI-related trade issues. While hard-law commitments are crucial for the long-term development of global trade, one should not overlook the role of soft law type of arrangements in moderating trade conflicts. Trade negotiations are just one among other instruments to achieve greater coherence—mutual learning and information sharing through trans-governmental networks, legal translation or otherwise have already been seen in dealing with other emerging challenges such as Fintech and cybersecurity.

But there are some caveats to these solutions. The rapid speed of technological advancements means these solutions are not intended to be written in stone. They must be nimble, and ready to respond at different times and contexts.

The potential radical disruption posed by AI, and in particular the distribution of high-tech development in countries, means a core challenge remains to ensure the institutions and rules are designed to benefit the most rather than the few.

The above solutions should of course be accompanied by appropriate mechanisms to build the trust of privacy and data protection and facilitate cross-border data flows. This is not easy, either, as the importance of data and AI has gone beyond the commercial sense by touching upon geopolitical complexity.

The hard question facing the WTO policymakers then is how to embrace such pluralism while resolving AI-related trade conflicts.

In the meantime, however, one should bear in mind different WTO Members’ capacities to manage the pacing problem and more crucially, the underlying dynamics that reshape the political economy between those haves and the have nots in the age of AI.

- Authored by Dr Han-Wei Liu, Lecturer, Monash Business School. This research, co-authored with Ching-Fu Lin from the National Tsing Hua University in Taiwan, was first published in the Harvard International Law Journal.

Trending

Daily startup news and insights, delivered to your inbox.