By Joshua Krook, University of Adelaide

The story of Yumiko Kadota, whose gruelling schedule as a Sydney hospital registrar included clocking up more than 100 hours of overtime in her first month, has highlighted the punishing work schedules required in the medical profession.

Research indicates working more than 48 hours a week is associated with significant declines in productivity, more mistakes and more mental health problems. Yet the Royal Australasian College of Surgeons reckons working up to 65 hours a week “is appropriate for trainees to gain the knowledge and experience required”.

It’s an attitude that explains why a 2017 audit found more than 70% of surgeons in public hospitals were working unsafe hours. And it’s symptomatic of many areas where pushing the hours envelope is seen as part of the job.

Last month, for example, a study by the Australian Transport Safety Bureau found almost one in four long-haul pilots reported working on less than five hours of sleep in the previous 24 hours – putting them in the risk zone where fatigue leads to impaired performance.

Meanwhile, two of Australia’s largest law firms are being investigated for overworking staff. At King & Wood Mallesons in Melbourne, lawyers working on the banking royal commission were reportedly sleeping in their offices overnight, too tired to go home. At Gilbert + Tobin Lawyers in Sydney, it is alleged lawyers were resorting to drugs and other supplements to cope with fatigue.

Other areas in which long hours are common are in mining, farming and construction. All up about 13% of the workforce – 19% of men and 6% of women – are working 50 hours or more, putting themselves, and others, at risk.

What’s the damage

After a century of “scientific management” you might think that more attention would be paid to the scientific studies on working long hours.

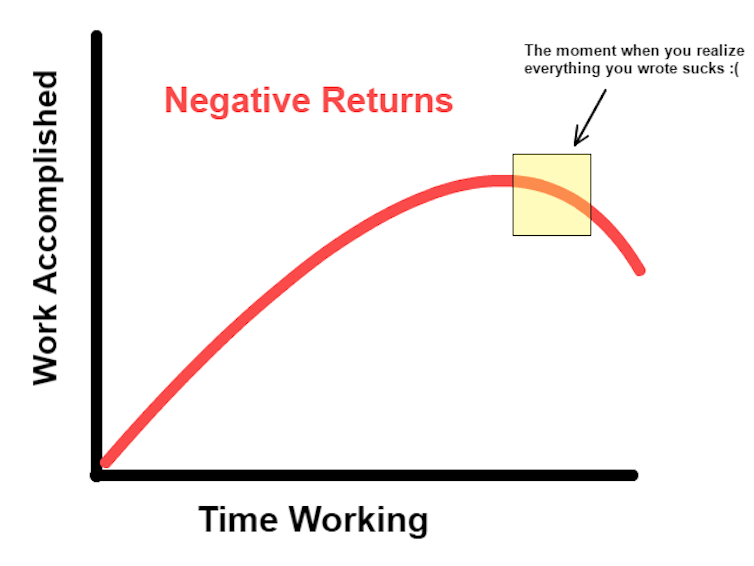

The relationship between work hours and productivity follows the economic law of diminishing returns. Productivity peaks at a certain point and then declines. Work too long and you get to the point where you’re achieving nothing; or are even doing damage.

The Observer

This is what the research literature tells us:

- After working 39 hours a week, mental health tends to decline.

- After 48 hours, job performance begins to rapidly decrease. There are more signs of depression and anxiety, and worse sleep quality associated with long-term health risks such as cardiovascular disease, type 2 diabetes and cancer.

- Working more than 10 hours a day increases the risk of workplace injury by 40%, and more than 12 hours a day doubles it.

- Longer working hours harm relationships, erode job satisfaction and contribute to depression, including increased suicidal thoughts.

A rule made to be broken

All of this research shows there’s good sense in Australia’s federal Fair Work Act (s. 62) capping the standard work week at a maximum of 38 hours.

But that maximum is easy to flout. The act also says an employer can require an employee to work “reasonable” extra hours. Determining whether they are unreasonable depends on 10 factors, including a risk to health and safety, family circumstances, the needs of the business, compensation, the usual patterns of work in the industry and “any other relevant matter”.

The law says an employee can refuse to work more than 38 hours a week, but in practice that rarely happens.

You may be happy to put in more hours because you are compensated. You may even do it “voluntarily”, because you see it as a path to promotion, or the way to keep your job. You may be enmeshed in a “first in, last out” culture, where it’s a competition to show your devotion to your job through the number of hours you work.

As a result, Australians work an average six hours of unpaid overtime a week.

Gaming the system

Management practices can promote an overtime culture without explicitly flouting the law.

One way is to scrutinise an employee’s working hours, such as using a billable hours system. This is common in law firms and other professional services. Clients are charged by the hour (or six-minute increments, as is the case in law firms) for the time an employee spends working on a matter. It puts pressure on a conscientious employee to do any work not related to a client in their own time. An employee may also under-report hours so as not look slow or unproductive to a manager.

Another way is through using casual or contract workers. Such employment can result in workers doing more hours than what they are paid for, either because they have underquoted to get the job, or are working on a fixed contract where the employer has defined how long it should take, or they feel the need to prove their worth to ensure they get more work.

Changing attitudes

State and federal government agencies, including the Fair Work Ombudsman and Safe Work Australia have broad powers to investigate worker health and safety (including overtime).

But for those powers to make a difference, these agencies need more resources to actually do investigations and greater powers to issue fines and corrective measures to companies where overtime is endemic. There’s no reason hours auditing couldn’t be a more routine procedure, much like food health and safety regulators inspect restaurants.

But more than that we need a change in the cultural attitudes that promote long hours as necessary, acceptable or heroic – even when someone doing their job while overtired and fatigued, such as a surgeon or pilot, is downright scary.

Joshua Krook, Doctoral Candidate in Law, University of Adelaide. This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

Trending

Daily startup news and insights, delivered to your inbox.