Global jostling involving companies and governments of many countries is underway that is more far-reaching than what occurred over oil in the first half of the 20th century.

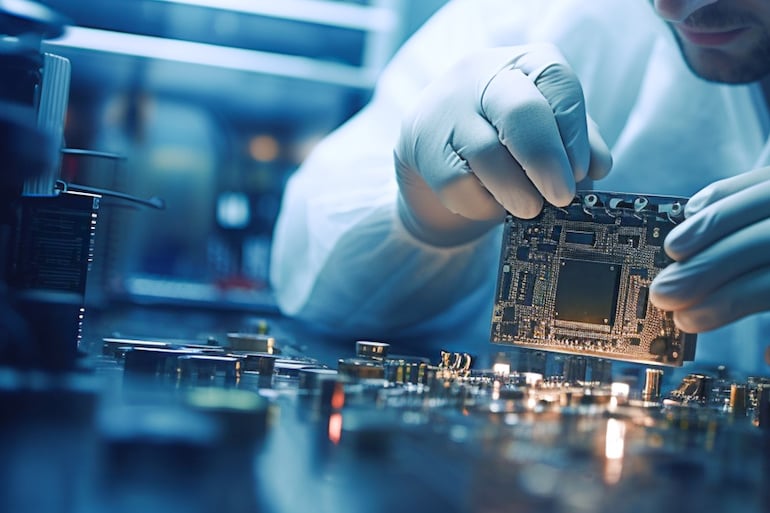

It’s in an industry that will drive the development of tens of billions of products over the next few decades – semiconductors.

This is because the next generation of semiconductors is powering the increased need for processers, sensors, and memory devices that touch just about every sector – for example, mobility, big data, AI, computing and storage, wireless and wired communication, industrial, automotive and consumer electronics, and health.

The semiconductor market alone across these industries is estimated to grow to over US$1 trillion by 2030.

Semiconductor companies include foundries (or ‘fabs’), capital equipment providers, integrated device manufacturers (IDM), micro-processing units (MPUs) and memory producers, and fabless companies (those that have no production assets).

The accelerating development involves eye-watering numbers. For example, the US Biden administration has established the US CHIPS Act & EU Chips Act that will boost new fab construction and advanced R&D in several countries to about US$97 billion and 12 fabs over the next few years.

Fabs costs billions to build. South Korea is planning 10 new fabs with US$260 billion in government investment. Japan and Taiwan are planning another 15 fabs. The EU has four more in planning stages, Singapore is also building one. And China is looking to construct 10 fabs of its own.

Trailing the world

Australia has fallen behind other countries like Taiwan, Germany, the Netherlands, the US, Japan, South Korea, and China, mostly in terms of the manufacturing of chips through foundries and equipment.

Yet, there is still an opportunity for Australia to capitalise on the rise in demand for semiconductors worldwide by complementing, rather than competing against, this fab construction. The secret lies in shaping policies that create a leading technology development ecosystem which feeds into the global supply chain across semiconductors, memory, and quantum technology – the most advanced applications of semiconductors.

Australia could focus on an advanced technology research ecosystem to support fabless semiconductor companies. Coincidentally it is memory and fabless semiconductor companies that have seen the most economic profit from 2015 to 2019 at US$94.9 billion and US$81.6 billion, respectively.

Fabless semiconductor companies make designs for chips, protect these designs with patents, and outsource the fabrication and manufacturing of the chip hardware to external foundry partners for test runs for scalability and then package, test, and send the chips off to the customer.

An advantage fabless semiconductor companies is lower capital expenditure, since they do not spend money on the upkeep or development of foundries and equipment, and focus most of their costs on the higher value added innovation in product development.

Currently, Australia already has some financial initiatives to help spur the local semiconductor sector. For instance, the Australian Tax Office (ATO) has an R&D Tax Incentive that it provides as an annual cash rebate for eligible R&D activities conducted by Australian companies.

Australia also has an AU$15 billion infrastructure fund to help ensure the long-term growth of the country’s advanced manufacturing sector and some of these funds include semiconductor spending.

But Australia does not necessarily have to spend too much money to create its own semiconductor industry, particularly if it chooses to focus on the development of fabless semiconductor companies.

Australia can create the environment to foster more fabless semiconductor companies by forming the right policies to facilitate it in the country’s start-up sector. Fabless semiconductor companies would not only work to develop their designs in partnership with Australian universities, but the companies could create new ideas borne out of fundamental research.

Australia already has a solid starting point; it has strong universities and well educated and capable people. Therefore, it can create better conditions to develop technology hardware and software and equip its people with the skills by:

Focus on the industry

If there is more of a focus on the semiconductor industry within Australia and the opportunities it could present to people wanting to get into scientific research and product development, it would boost recruitment.

The government, in conjunction with a critical mass of companies and universities, could run more advertising campaigns on experiential programs that help people specialise in semiconductor design.

Companies could also feature as case studies of what they are achieving and how employees are progressing their careers at Australian fabless semiconductor companies. A good example of this is industry access to the Australian Nanofabrication Facilities including research and prototyping semiconductor foundries.

A more effective regulatory framework

The government could work with Australian semiconductor companies to draft legislation that would help grow the industry. Or companies could work with the government in changing existing regulation to help create the conditions for enhanced research and design of chips.

There must be a firm commitment to linking the semiconductor industry with Australia’s GDP over the long-term. Lessons can be learned from countries like South Korea.

Develop stronger IP law

Once a fabless semiconductor company has its own design, that design needs to be protected.

The government could help create IP law that better protects Australian made chip designs and establish barriers to entry against foreign competitors.

The EU, US, and UK are unashamedly proactive when it comes to semiconductor IP protection, while balancing competitive global operations for its multinational organisations.

Building a disruptive space

When taking these measures into consideration, the semiconductor industry will function best if it is a disruptive space.

Creating an ecosystem where smaller and more medium sized companies compete against each other will not only establish more of an equal playing field, but it will foster stronger competition and therefore more advanced chip design.

By increasing focus on the industry, creating better regulations, developing globally competitive IP, and making it disruptive, Australia could be a key player in innovation ecosystem that advances the world’s semiconductor industry and reap the big rewards, both economically and socially, that it will bring.

* Dr Mohammad Choucair is CEO of ASX-listed Archer Materials.

Trending

Daily startup news and insights, delivered to your inbox.