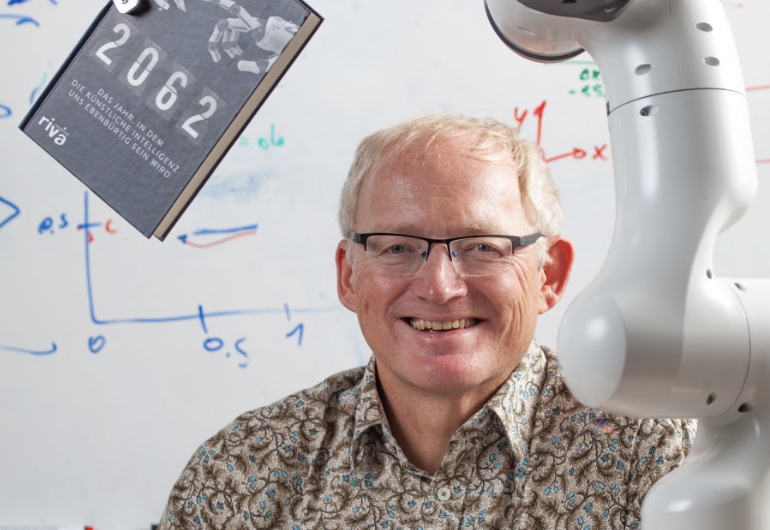

Toby Walsh is one of Australia’s most well-known experts on artificial intelligence and his latest book Faking It: Artificial Intelligence in a Human World aims to dispel the common illusion that machine intelligence is comparable to human intelligence.

It’s an illusion deeply embedded in the history of AI that could have disastrous consequences, Walsh believes, unless we grasp what the technology actually is, rather than what we think it could be.

The “artificiality of artificial intelligence” is what makes it so powerful and dazzling: computers don’t forget like we do, they aren’t ruled by emotion or bias, and they work at the speed of electricity not the speed of biology.

“By abstracting intelligence, we can hand over many tasks to machines,” Walsh says, lamenting that instead of building machines “that can take over many of the dirty, dull, difficult and dangerous jobs, and make our society more just, fair and sustainable”, we have collectively stumbled – or been led – into the trap of anthropomorphism.

Why is this a problem? Because, as Walsh explains, AI isn’t a faster, more powerful version of human intelligence – it’s fundamentally different.

What humans lack in raw speed and storage capacity, we make up for in adaptability and efficiency.

We can apply knowledge across domains and we don’t need to be shown a billion pictures of an object to start identifying other similar ones.

Human intelligence also tends to “degrade gracefully” while machine intelligence can be remarkably brittle, breaking in unexpected – and potentially disastrous – ways.

Faking It by Toby Walsh

Our tendency to anthropomorphise AI, to see “the ghost in the machine”, means we often fail to adequately make these distinctions and, as a result, risk relying too much on what we imagine AI to be rather than what it really is.

Walsh presents this thesis with the humour and breadth of knowledge of an expert who is passionate and enjoys speaking about his field.

Throughout Faking It, Walsh explains how AI has always been about faking human intelligence – calling this fakery one of the field’s “original sins” – and tries, like someone exposing a magic trick, to show the reader how we have been fooled into propagating a myth that helps line the pockets of venture capitalists and irresponsible technology companies.

Faking It is intended for a general audience and isn’t particularly technical.

The book doesn’t provide detailed descriptions of the architecture of neural networks, for example, instead giving his readers an erudite and contemporary history of AI that can – for someone who has followed AI closely over the last 12 months – illicit the urge to impatiently ask ‘okay, but what do we do about it?’

That urge is largely countered by Walsh’s funny, engaging writing style and, in the book’s final chapters, he provides ways for us to see beyond the illusion.

How to solve a problem like AI

For starters, Walsh urges us all to “be more aware of how easily computers can fake it, and of our own wishful thinking about how ‘human’ their machine intelligence is”.

He wants tech professionals in particular to “stop anthropomorphising the technology that we build,” saying the language we adopt can help change how everyone understands AI.

“We speak about a chatbot ‘understanding’ a sentence, a ‘self-driving’ car, the computer-vision algorithm ‘recognising’ the pedestrian, and the possibility of robot ‘rights’,” Walsh writes.

“In reality, chatbots don’t understand language. There is no self – no person, no sentient, self-aware intelligence – driving the car, even if the car is driving itself. Algorithms don’t actually recognise objects. And robots need rights about as much as your toaster does.”

This last point Walsh makes passionately, warning us not to get sucked into erroneous conversations about whether machines deserve rights typically afforded to humans or animals.

“Rights are best given, as they are now, only to sentient beings that can experience pain and suffering,” he says.

As far as regulation goes, Walsh writes that it is to be expected, especially in response to tech companies that “rush ahead, give up on transparency and act recklessly”.

In particular, he calls for ‘Turing Red Flag laws’ that would “ensure that deep fakes were identified as fake, that AI bots weren’t designed to pretend to be real people, and that warnings were provided to advise us that any such bot was artificial”.

That name comes from previous laws that required people to walk in front of cars carrying a red flag to warn other people that a car was coming.

As Walsh puts it, the red flags existed “to warn other road users of the novel technology that was arriving, which otherwise might cause panic”.

In the intervening decades, rules and regulations around car safety have continued to develop and, as a result, the technology has radically altered how our cities are designed and how we live our lives.

AI likewise has the potential to fundamentally change society, but it’s up to us to make sure artificial intelligence works to benefit human intelligence and not the other way around.

Faking It is published by La Trobe University Press.

Trending

Daily startup news and insights, delivered to your inbox.