The Australian government does not understand what a ‘startup’ actually is. This is the sentiment that’s been echoed across Australia’s startup community and is considered the entry point to a bigger problem – policy.

There are a number of ways policy fails our startups – from tax obligations and limited public funds to the lack of entrepreneur visas and employee share schemes. But new policies cannot be introduced until policymakers have spoken to startups about their past achievements, current needs and future plans. Before that, they need to be clear on the definition of startup and why this sector needs support and nurturing. The answer to the latter is: to safeguard the Australia’s long-term economic prosperity.

A PwC report from April 2013 revealed that tech startups have the potential to produce 4% of Australia’s GDP (Gross Domestic Product) by 2033. Commissioned by Google Australia, the report estimates that in ten years, tech startups could contribute AUD$109 billion and 540,000 jobs to the Australian economy.

Defining a ‘startup’

#StartupAUS, the non-for-profit body formed in 2012 with the help of Google’s Head of Engineering Alan Noble, defines startup as an emerging high-growth company that is using technology and innovation to tackle a large and often global market.

So, according to #StartupAUS, there are two defining characteristics of startups: 1) they have great potential to grow (or in other words, are highly scalable); and 2) they create disruptive innovations that often reshape the way entire industries work.

This definition of startup aligns with what Paul Graham, Co-Founder of American accelerator Y Combinator, wrote in his essay Startup = Growth. In short, he describes startup as “a company designed to grow fast”; and for a company to grow fast, they will need to create something they can sell to a big market.

This is where technology comes in. Although Graham doesn’t explicitly state in the essay that startups are responsible for creating new technology, there are clear synergies between startups and technology. Compared to the local cafe or barbershop, technology has greater global potential; it can be rolled out into different markets much faster. Therefore, technology is highly scalable – the first defining characteristic of a startup.

Noble believes, “Technology is invariably crucial because it provides the competitive advantage and leverage necessary to grow quickly.”

He stressed further that ‘technology’ is not confined to software, hardware, mobile and net; it encompasses biotech, clean tech, advanced manufacturing, or anything where innovative technology provides a competitive advantage.

Startup vs. Small Business

Although ‘startup’ is a hot topic in Australia, it is too often confused with ‘small business’ – a mistake I have made myself. Kim Heras, General Partner at 25Fifteen, said most startups are small businesses, but most small businesses aren’t startups. This is because most small businesses are service businesses – restaurants, electricians, plumbers etc.

This is not to say that small businesses aren’t tech-savvy. As Noble pointed out, “[W]hile small businesses often utilise innovations, they typically do not create disruptive innovations of their own, and certainly not “new to world” truly differentiated innovations.”

It’s true that all businesses want (and need) to grow, but small businesses aren’t designed to grow at the speed of startups. In fact, small businesses cannot handle high-growth. If even 500 customers walked into a cafe, the business would crash. Whereas, if you look Canva, which launched less than a year ago in August, this startup is well on its way to gaining 1 million users (currently sitting at over 600,000). Due to the inherent nature of technology, tech startups can handle the growth that small businesses can’t.

This is one of the reasons why startups have different pain points to small businesses, and cannot be put into the same category if we really want this sector to flourish.

“It’s important to carefully define what we mean by ‘startup’ because startups have the potential to generate so much economic wealth. Although startups naturally start out as small companies, unlike other small businesses, they have great potential to grow,” said Noble.

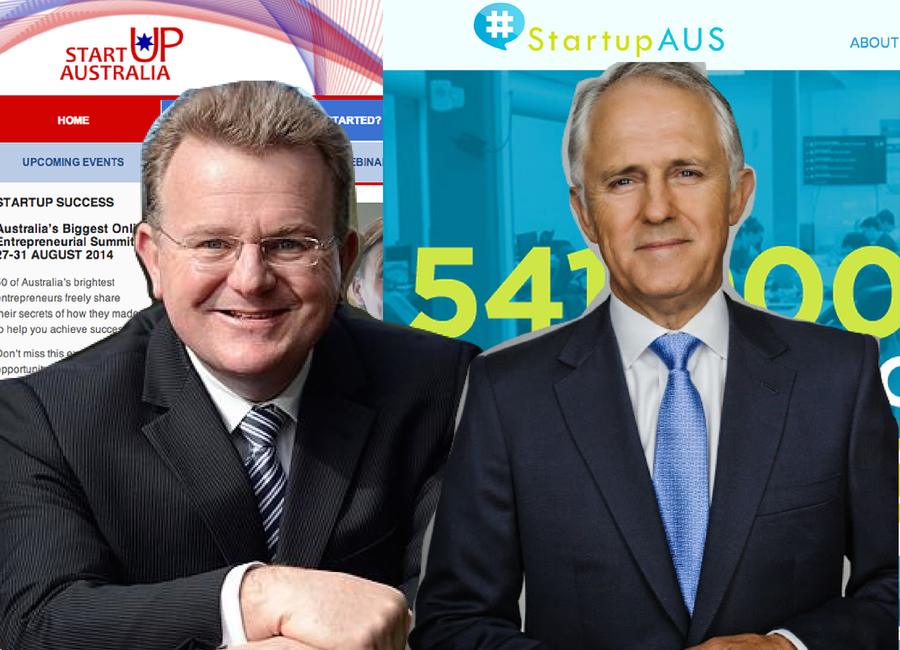

Start Up Australia, #StartupAUS – Where’s the consistency?

Although startups and small businesses have different interests and needs, at this point, startup is being squeezed into the broader category of small business or is used interchangeably with small business. The latest organisation to do this is Start Up Australia.

In fact, today marks the launch of Start Up Australia, a non-for-profit organisation, national campaign, and educational institution that aims to foster a culture of entrepreneurship and innovation in Australia. The organisation was launched officially by the Hon. Bruce Billson MP, Federal Minister for Small Business.

Founded by entrepreneurs Brian Sher, Miriam Feiler, Siimon Reynolds, Larry Bloch, John Studdert, and George Wahby, Start Up Australia is the latest edition to the global startup movement which pioneered in the US under the moniker ‘Startup America Partnership’. President Barrack Obama launched Startup America Partnership to help mitigate the effects of the Global Financial Crisis. Due to lack of job security, starting up was considered the pathway to a more economically-sound nation.

The founding board of Startup America Partnership includes Reed Hastings, Founder and CEO of Netflix, Reid Hoffman, Executive Chairman and Co-Founder of LinkedIn, Michael Dell, Chairman of the Board and CEO of Dell Inc., and Pamela Contag, CEO of Cygnet Biofuels, among other big names. If these names aren’t suggestive enough, you can take a quick glance on the website and it’ll become apparent that Startup America Partnership is heavily focused on tech startups. You won’t notice ‘small business’ printed anywhere.

Although each Start Up Nation is a localised version of a global movement, upon closer analysis, it appears that Start Up Britain and Start Up Australia have diverted slightly from the original focus of the movement. The British and Australian editions target both small businesses and startups – or more broadly entrepreneurs.

Before going ahead, let’s look at the word ‘entrepreneur’. Oxford defines ‘entrepreneur’ as someone “who sets up a business or businesses, taking on financial risks in the hope of profit”. Judging by this definition, an entrepreneur is really just a businessperson. While startup founders are entrepreneurs, not all entrepreneurs are building startups.

Entrepreneur, then, is a very big category encompassing founders of all kinds of businesses. Tech startup founders fall into a sub-category of ‘entrepreneurs’ and so does small business owners.

“While anyone who starts a business may be considered an ‘entrepreneur’, it is tech entrepreneurs who found startups, and the latter are currently only a tiny proportion of entrepreneurs in Australia,” said Noble.

This is what Miriam Feiler, Co-Founder of Start Up Australia, explained to me in an interview: that Start Up Australia is an open community, inclusive of all entrepreneurs including tech startup entrepreneurs.

At the launch, Sher was careful to point out that Start Up Australia is interested in all sectors: high tech, low tech, online, offline, traditional and new.

Start Up Australia certainly deserves merit and admiration for what it is trying to achieve. The organisation is trying to encourage Australians to view entrepreneurship as an exciting and important career path, and subsequently motivate people young and old to start new businesses. They also want to be the ‘cheerleaders’ for entrepreneurs, and fully support them throughout their entrepreneurial journeys.

At the launch today, Sher summed up Start Up Australia quite succinctly when he said “[we want to] create a nation of problem-solvers” because it is through problem-solving that great businesses emerge and grow.

But what is confusing is the name ‘Start Up Australia’ which can be seen as a derivative of #StartupAUS – or vice versa. Feiler said that ‘Start Up’ stands for ‘starting up the Australian economy’, not necessarily ‘startup’. She added that the space between ‘start’ and ‘up’ was a deliberate choice on their behalf. But it’s too easy to think that by ‘Start Up’ they mean ‘startup’ – not only because the movement began with the intention of growing the tech startup ecosystem in the US, but also because Start Up Australia has mentioned ‘startups’ repeatedly in mission statements.

I asked Feiler what Start Up Australia defines as a startup, and she said “any business across any sector that is in the early stages of growth.” This suggests that she considers startup as a business that is starting up – a common misconception in Australia.

She added, “Obviously the tech startup community is included in that. This is a national campaign that really wants to reach the millions of small business owners and entrepreneurs around the country, regardless of what industry sector they’re in.”

This statement once again throws startup into the broader entrepreneur and small business mix. The problem then becomes that we don’t have a consistent definition of startup in Australia. Without a consistent definition, the government is not going to be able to identify what needs to be done to help our startup community. They may even think ‘startup’ is a buzzword or a fancy way of saying ‘small business’.

Think of it this way: If you know nothing about ‘rocket science’, and an ‘aerospace engineering’ student asks you to help them with their project, you’re probably going to look the other way and run. So can we really blame the government for not understanding what a startup is? If anything, they should be blamed for not trying hard enough to understand this sector when all we’re doing is shouting for attention.

Although Start Up Australia has no relation to #StartupAUS, it’s easy to get them mixed up. When news spread about Start Up Australia’s inaugural launch, there were whispers in our startup community, with many wondering ‘why are there two bodies representing such a small sector?’ The reality is that Start Up Australia and #StartupAUS are not competitors. They happen to have very similar names. And I don’t believe one copied the other. Start Up Australia has been 18 months in the making, which isn’t all that different to #StartupAUS. Besides, Start Up Australia is part of a global movement which kicked off in 2011. There are now 44 Start Up Nations – including Canada, Korea, Chile, Malaysia, and more.

#StartupAUS focuses on tech startups, which according to Start Up Australia is a very small proportion of the people they are targeting.

Noble says StartupAUS looks “holistically at what we need to grow the tech startup ecosystem.” This includes both long and short tail advocacy efforts around increasing STEM (Science, Technology, Engineering and Maths) and in particular CS (Computer Science) in schools and universities. #StartupAUS also advocates for regulations such as ESOP (Employee Stock Ownership Plan) and 457 Visa change to support talent attraction and retention by publishing reports like ‘Crossroads’ and responding to government submissions that affect startups like the EIP (Entrepreneurs’ Infrastructure Programme). Startup Spring, a national festival of events that showcases startups, is a #StartupAUS initiative aimed at raising awareness about startups.

Start Up Australia, on the other hand, is kicking off its mission to help small businesses through education. The organisation is offering a 12 week Small Business Master Class Accelerator where members get 12 30-to-45-minute video lessons sent to them week by week. Start Up Australia is also hosting an online Business Success Summit at the end of August where 50 of Australia’s top entrepreneurs share their journeys via pre-recorded videos. All educational resources are free to access for members of the Start Up Australia community.

So how are they making money? Apparently, they’re not. Start Up Australia claims to be a non-for-profit organisation fully funded by our country’s corporate sector. Its founding partners include MYOB, American Express, Fortune Institute, and the Australian Chamber of Commerce and Industry.

“Australian corporations are backing us to deliver free access to resources, expertise, and practical advice for people wanting to start a business,” said Feiler.

The important thing to remember here is that Start Up Australia is “led by entrepreneurs, for entrepreneurs”. The organisation’s mission is similar to Jo Burston’s Rare Birds which will be launching officially later this year. Both Start Up Australia and Rare Birds claim to be a global movement and both claim to be created by entrepreneurs for other entrepreneurs. Rare Birds, however, is very much a business, but a business that exists for a purpose. So it could be seen as a social enterprise.

Based on initial conversations with Feiler and Burston, I feel that Rare Birds is much clearer in its mission, and does not in any way confuse startups with small businesses. Rare Birds is looking holistically at what Australia’s economy needs.

“Rare Birds will be a disruptive agent of change, creating real social and economic impact via mentorship, funding, storytelling, community and partnership with individuals and thought leaders with aligned values and purpose,” is the official mission statement provided by Rare Birds.

The company will is operating on four pillars: Storytelling, Funding, Mentorship and Community.

Burston says “entrepreneurs pass information through stories”. As such the storytelling aspect of the business is about telling “captivating, engaging and intelligent accounts of current and emerging entrepreneurs.” The plan at the moment, is to a book each year featuring 50 women entrepreneurs and telling their stories. A second annual volume will showcase and encourage 30 emerging women entrepreneurs.

The second pillar is funding. Rare Birds will act as a gateway to funding and investment for startups. This means that entrepreneurs will have access to a diverse pool of Angel and VC investors, as well as other sources of funding, should they need it.

Rare Birds will also match entrepreneurs with the right mentors to offer insights and guidance throughout their journey. The mentoring won’t be as structured as accelerator programmes – where mentors go around the room to talk to each startup. Rare Birds will be creating mentoring programs that “are self-sustaining and self-managed that exists as a measured transfer of experience and knowledge”.

The last pillar, Community, is about education. Rare Birds aims to have the largest database of women entrepreneurs globally, and will act as a platform for conversation. This will be achieved by creating an open source environment with no barrier to entry and where entrepreneurs have no shame in asking questions and sharing experiences.

The forum on the site will help create this sense of communal belonging. It will also be a way for entrepreneurs to refer each other’s businesses, Burston says. If someone wants a new accountant, they can ask other entrepreneurs who they’re using and why.

I’ve tried to understand what Start Up Australia is actually going to do other than host online business training events, and it’s still not clear. At the launch today, they mentioned that they are already engaging in discussions with government officials, but what the subject of the discussions was not revealed. From my understanding, Start Up Australia, like Startup Muster, launched by Fishburners General Manager and AdMuncher Founder Murray Hurps earlier this year, will be collecting data on startup companies to help guide new policy.

Start Up Australia also want to “collaborate with the community/ecosystem”; it will be working with incubators and accelerators as well as engaging with the corporate, education and financial sectors. But how? We will need to wait and see.

Heras made a point that it’s too soon to judge Start Up Australia. Given the organisation only launched today, it’s definitely a good point.

“They should be judged, as all community focused organisations should, on what they achieve for the community itself,” Heras said.

He added though that he wasn’t sure that there is any organisation that fully represents the sector just yet.

“StartupAUS and Startup Victoria are doing a good job – but by no means should they have some sort of exclusive right to do that.”

Fragmentation

In the interview I had with Feiler last Friday, I asked whether she thought Australia’s startup ecosystem was fragmented. Without much conviction, she agreed.

Her exact words were, “Australia’s a big country. We have states. We have communities operating in major cities. We have communities operating in regional centres and even in regional suburbs. And they’re all doing fantastically in engaging their local communities…I think there’s a lot of strength in collaboration.”

“I’m hoping people will see Start Up Australia as an organisation to approach as we already have and will continue to engage with every organisation – whether it’s a co-working space, an incubator, a venture capitalist, a startup support organisation, or a small business support organisation – to raise the profile of entrepreneurship and help more people start and grow a business”.

I absolutely believe that Start Up Australia is trying to unify us; they want to bring all parts of the ecosystem together. Mat Beeche, Founder of Shoe String Media, wrote in a previous article, “Togetherness is a beautiful thing; it has the ability to catapult an ecosystem into a different playing field”.

The problem, though, is that the startup ecosystem is different to the small business ecosystem. Perhaps, Start Up Australia is referring to the broader business ecosystem, where startups and small business can be seen as ‘micro-ecosystems’. Regardless, in trying to make Australia less fragmented, are they exacerbating the fragmentation?

There are multiple organisations that are trying to own the startup space, but there is little collaboration. And I believe that unless Start Up Australia and #StartupAUS collaborate – in spite of how confusing that may be due to names – it will make our startup ecosystem more fragmented.

Then again, collaboration will only work if there are synergies between the two bodies. And now we come back to the definition of ‘startup’.

When it comes to communicating with the government about what the term ‘startup’ is, #StartupAUS has been very clear and concise in their message – as evidenced by their publication discussions with Malcolm Turnbull, Minister of Communications.

Based on today’s speech by Bruce Billson, Federal Minister for Small Business, it seems that he understands the term ‘startup’ in a different way – like ‘starting up a business’.

Two different conversations happening in parallel, using the same term, can be problematic.

Could Start Up Australia be a case of the right mission using the wrong name or are our government officials savvy enough to recognise the difference between Start Up Australia’s and #StartupAUS’ use of ‘startup’?

—

Update: EIP was formerly referred to as the Education Inclusion Plan, when in fact it stands for the Entrepreneurs’ Infrastructure Programme. Apologies about the mixup.

Trending

Daily startup news and insights, delivered to your inbox.