University of South Australia biomedical engineer Professor Benjamin Thierry is leading a study with researchers from Harvard University using the microfluidic technology to test the effects of different levels and types of radiation.

A microfluidic cell culture chip closely mimics the structure and function of small blood vessels and is contained within a disposable device the size of a glass slide.

To date, scientists have relied on testing radiotherapy on cells in a two-dimensional environment on a slide.

Professor Thierry said the organ-on-a-chip technology could reduce the need for animal studies and irrelevant invitro work, both of which had major limitations.

“An important finding of the study is that endothelial cells grown in the standard 2D culture are significantly more radiosensitive than cells in the 3D vascular network. This is significant because we need to balance the effect of radiation on tumour tissues while preserving healthy ones,” Prof Thierry said.

The findings, published in Advanced Materials Technologies, will allow researchers to fully investigate how radiation impacts on blood vessels and – soon – all other sensitive organs.

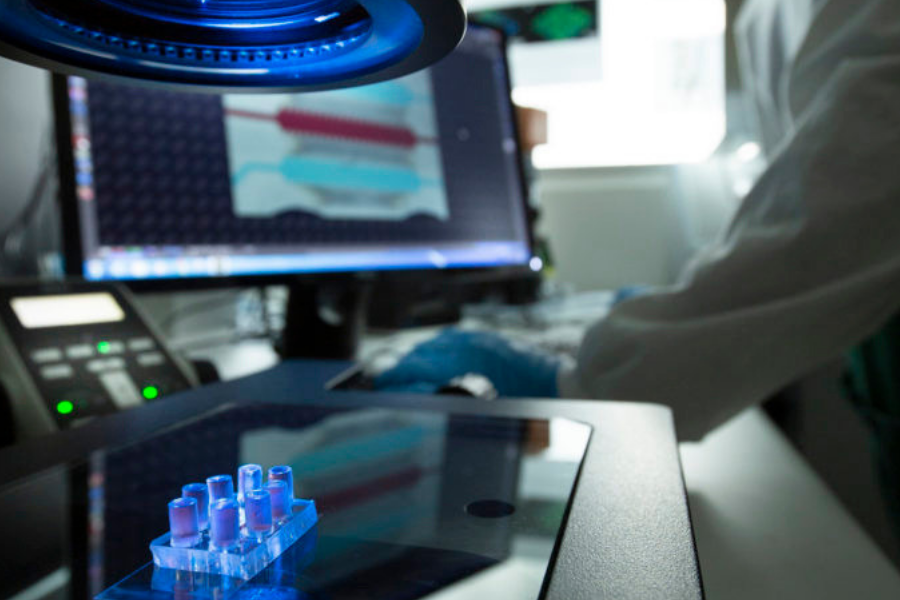

UniSA bioengineer Dr Chih-Tsung Yang, the co-first author of the study, pictured with the microfluidic cell culture chip in the foreground. Picture: Joe Vittorio

“The human microvasculature (blood vessel systems within organs) is particularly sensitive to radiotherapy and the model used in this study could potentially lead to more effective therapies with fewer side effects for cancer patients,” Prof Thierry said.

More than half of all cancer patients receive radiotherapy at least once in the course of their treatment. While it cures many cancers, the side effects can be brutal and sometimes lead to acute organ failure and long-term cardiovascular disease.

Prof Thierry’s team, including University of South Australia Future Industries Institute colleague Dr Chih-Tsung Yang and PhD student Zhaobin Guo, is working in close collaboration with the Royal Adelaide Hospital and Harvard University’s Dana-Farber Cancer Institute with the support of the Australian National Fabrication Facility.

“Better understanding the effect of radiotherapy on blood vessels within organs – and more generally on healthy tissues – is important, especially where extremely high doses and types of radiation are used,” Dr Yang said.

The researchers’ next step is to develop body-on-chip models that mimic the key organs relevant to a specific cancer type.

The South Australian node of the Australian National Fabrication Facility (ANFF-SA) is one of eight university-based hubs around Australia, which are funded by Commonwealth and State Governments, the CSIRO and participant universities.

Complementing the University of South Australia’s Future Industries Institute’s research infrastructure at its Mawson Lakes campus, ANFF-SA started out a decade ago specialising in microfluidics.

While this remains a key strength, ANFF-SA’s expertise has grown to include lab-on-a-chip technology, advanced sensing, functional coatings and separation science.

Products developed in recent years include a microfluidic device offering gene-modified cell therapy, a non-invasive device to test urine for the presence of bladder cancer cells, a micro needle for an in-home blood-testing platform and a microfluidic chip for high-value mineral extraction.

Image: UniSA bioengineer Dr Chih-Tsung Yang, the co-first author of the study, pictured with the microfluidic cell culture chip in the foreground. By: Joe Vittorio

Trending

Daily startup news and insights, delivered to your inbox.