There has been a paradigm shift in Australia’s startup sector in the last few years. Just five years ago, there were a handful of pioneers dedicated to supporting the development of tech startups. Today there is a quickly growing number of participants, from university incubators and coworking spaces to industry-specific innovation hubs and corporate accelerators.

Scaling the startup ecosystem requires two necessary ingredients; 1) enough raw founder talent and 2) the resources, both venture capital and experienced individuals, to nurture growth. Scaling without enough of either creates a quality vs quantity dilemma.

I recently presented a study at an international innovation conference in Jakarta that sheds some light on the issue by looking at the original and the most successful startup accelerator, Y Combinator (YC). The aim was to look at the tension that exists between raising high growth, disruptive companies and doing that at scale.

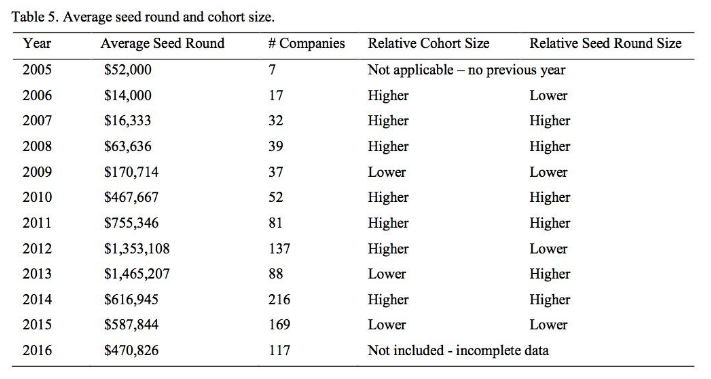

To do this, I looked at data from YC over the last decade, sourced from Crunchbase, to investigate whether the increasing number of companies that YC accepts each year has an impact on the startups.

World’s leading accelerator

Y Combinator is the world’s leading accelerator program. Taking place twice a year in San Francisco, it has invested in over 940 companies including Dropbox, Airbnb, Coinbase, Stripe, and Reddit. Five hundred investors hear pitches from over 100 companies to decide who to invest in. The demand to get into the program is so strong that as few as 1 percent to 2 percent of applicants are accepted by YC.

YC’s companies are collectively worth over $80 billion and it has produced many companies with much higher valuations that other big US accelerators. Y Combinator has produced several billion dollar startups, whereas none of Techstars’ startups have passed the billion dollar mark.

Over the past decade the number of companies taking part in each Y Combinator cohort has also grown, from seven companies in 2005 to over 200 by 2014.

These large numbers, and the consistent approach taken to accelerating the participants, might appear to conflict with the goal of producing innovative and disruptive companies. After all, it suggests that resources – particularly time and attention from Y Combinator – must be spread thinner.

My Y Combinator experience

This research isn’t just academic: the company I cofounded was accepted into YC, and so knowing if the growing cohort size helps YC companies (or not) matters! From our experience, YC has a really strong focus on the basics of building a successful business, removing any distractions. There are no silver bullets.

YC is also about being surrounded by smart people who are invested in helping us create a product that people love. Advice isn’t sugar coated: this is important, as great companies are built by constantly focusing on what can be done better.

Instead of mentors, YC has partners. We had frequent access to great people – from the team who founded YC, through to the creator of Yahoo Mail, Google’s business product offering and the cofounder of Twitch (which when we met him, Twitch had just sold for $1 billion).

Can innovation scale?

There are obvious potential pros and cons associated with Y Combinator’s increasing cohort size. Larger cohorts mean more competition for funding. It also limits the amount of time for advice and mentorship. Advice can also end up being more generic and poorly suited to the unique needs of individual companies.

But when it comes to the hard numbers, it turns out there’s no negative correlation between the size of Y Combinator and the amount of money raised in subsequent seed rounds. In fact, each individual company seems to raise more when batches are larger. There’s also no negative relationship between cohort size and the average number of days for an acquisition.

So even though one might expect that the greater the number of companies, the greater the competition and lower average investment each would receive, this hasn’t happened. To date, the continued growth of Y Combinator appears to be a virtuous circle.

Lessons for Australia

Y Combinator has built its success in two potentially significant ways. First, having built a reputation as one of the best accelerators globally, it can attract the top tier of startup applicants as well as the most prominent investors.

Even as it has grown, the number of applicants has also grown, allowing it to maintain an acceptance rate below 3 percent. This is challenging for any Australian accelerator to replicate, with anecdotal evidence suggesting local accelerators can accept anywhere from five to 20 percent of applicants. We need to figure out how we can create the same focus on quality in Australia.

Secondly, Y Combinator strongly espouses independence and autonomy for the companies that participate in their program. Unlike many other accelerators which provide free or subsidised office space, Y Combinator does not.

Paul Graham, one of the original co-founders of Y Combinator, says this is essential for companies to develop their own unique culture. Greater independence may certainly help YC companies thrive.

For GO1, this helped us develop our own unique culture and environment. It wasn’t diluted by having lots of neighbours: we could focus on who we were, without distractions, but still benefit from the weekly founder dinners that YC hosts.

For most of the YC program we rented a two bedroom house in Mountain View, California, and had up to eight people living and working from it. Space was very cramped, but we got a lot more done by concentrating on our business, rather than being constantly in conversation with other startups working in completely different areas.

It’s not possible to simply replicate YC – we are not in Silicon Valley. But we should not ignore some of the lessons that we can learn for our own environment.

The Australian startup ecosystem has come a long way in the last five years. By continuing to focus on the details, expecting excellence, and maintaining our own unique startup culture, we can continue to grow our own startup ecosystem.

Image: Andrew Barnes, cofounder and CEO of GO1, an edutech startup and Y Combinator alum working in the online learning and education sector. Source: Supplied.

Trending

Daily startup news and insights, delivered to your inbox.