It’s never been easier or cheaper to furnish your home and stock your wardrobe, with fast fashion booming and stores like Kmart and Target waging an intense battle to see who can give shoppers the lowest price on the latest mass-produced decorative piece.

However, with this has also come a growing awareness of the problems around sustainability and ethics that arise in the creation of mass-produced items, leading some consumers to turn to outlets like Delpino’s, an ‘ethical department store’ allowing shoppers to browse and buy products according to their value set.

Also a contributing factor for others is taste, and wanting something one of a kind.

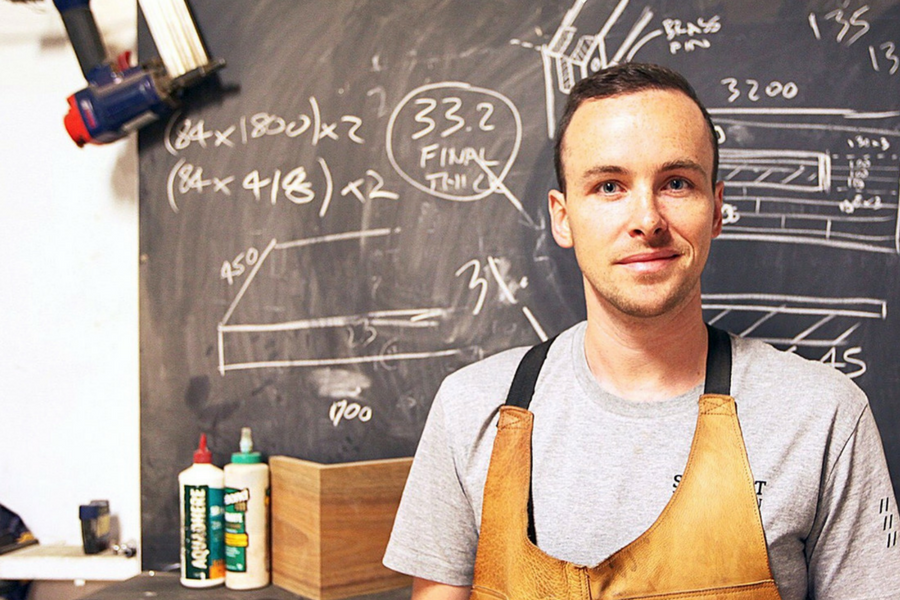

Providing consumers with an alternative to cookie cutter furniture is Melbourne’s Sawdust Bureau, described by founder Bryan Cush as a low-volume furniture studio that looks to “blur the boundaries between contemporary art, sculpture and architectural design”.

Cush founded Sawdust Bureau as an “experimental timber workshop” in 2013, while still working full time in architecture. For a time he partnered up with engineer Greg Bielawiec before going solo again in 2015.

“The driving force behind starting my business was born from the frustrations I faced during my spell working in architecture. The arduous process in constructing a building involves so many different parties, from developers to engineers, builders, neighbours, councils and so on, each protecting their own interests, meaning that the initial design concept can often be lost. For me, this whole approach to design was simply too laboured and stifled creativity,” he said.

His interest switched to furniture design through a combination of his grandfather’s influence, Cush said, with his grandfather also an architect turned furniture maker, and his participation in a course on timber furniture design as part of its Masters of Architecture at the University of Melbourne.

From here, Sawdust Bureau began with Cush renting a four-by-four metre workshop and getting a hold of tools secondhand. Upgrading the machinery piece by piece after a couple of commissions, the business was in 2015 awarded at Start Up Grant from the City of Melbourne that gave Cush the opportunity to turn it into a full time business.

Cush’s background in architecture led him to embrace technology in his work at Sawdust Bureau, a key part of which is 3D CAD – computer-aided design – modelling software, used as a design and documentation tool.

“It allows us to rapidly test conceptual ideas, quantify material costs, produce photo-renderings and 3D printed models to our clients all from within the same platform,” Cush explained.

“Traditional furniture design would have been drafted in 2D and then material cut lists and costs calculated manually, a tedious, laborious and static process, requiring manual updates each time the design is modified, whereas CAD software means the project is always live and up to date. Using CAD also helps to cut costs by reducing labour hours involved in manually calculating cut lists and also reduces off-cut wastage.”

The creation process begins with Sawdust Bureau holding a client consultation to develop a design brief in collaboration with the client. From there, concepts are developed in a sketchbook, then scanned via its HP OfficeJet Pro and used as a base to develop and explore the idea in CAD, Cush explained.

“This step might seem like a simple one, but this device really makes a huge difference to the entire process. The OfficeJet Pro lets me print on the move via the app, which means I can be in the timber yard or in a gallery and when I head back to the workshop, I can quickly grab the prints and get back onto the tools without delay. I can also print directly off a USB stick, again making it easier to feed into the design concept,” he said.

“Once the concept begins to take shape we will send the client rendered images for feedback. This is a fluid process and we try not to get fixated on any design ideas too early on in the process. After the client is fully satisfied at the final, developed concept we print out our cut lists and head for the timber yard to select the lumber for the piece.”

From there it’s the traditional carpentry work, from acclimatising and dressing the timber to setting out boards with aesthetics and grain orientations in mind, Cush said, then cutting before a dry test fit, and the “final glue up”.

“Latter stages of planning, scraping, and sanding focus on refining the piece down to the most minuscule details. The application of an oil finish gives the timber a pop of colour as the full depth of the grain is revealed, a definite highlight for any furniture maker,” Cush said.

Given the amount of work that goes into producing a piece, Cush said a key challenge for Sawdust Bureau is competing with imported, mass-produced furniture, while copyright and intellectual property (IP) are also of concern.

“We’ve found it possible to address the issue of mass production by tailoring our business towards customisation and educating clients on the benefit of sourcing materials locally and sustainably rather than contributing to unethical deforestation in the developing world,” Cush explained.

“The problem of IP is a much bigger cultural issue in Australia at the minute with many well known, high-street furniture stores openly ripping off internationally-protected works under the moniker of ‘replica’ with little or no legal consequence.”

This practice has recently been outlawed in Europe, with a European Union ruling last year extending copyright from 25 to 70 years after a designer’s death.

As legal startup LegalVision explained, the Designs Act 2003 requires a design to be registered before manufacturing; registering gives designers 10 years’ protection and the exclusive rights to make and sell this design themselves or license it to others for this period, however after this time designers are afforded little protection.

Registering a design or 3D artistic work industrially also means copyright – which is automatic in Australia and affords designers protection throughout their lifetime and for 70 years after their death – is lost, as LegalVision pointed out that dual protection isn’t possible. Another issue here is that copyright may not apply to a design industrially, but only to the drawing of the design.

For creators like Cush, these laws are a worry.

“If the Australian government doesn’t act soon then what hope do local designers stand in making a career here?”

In the meantime, the business has grown thanks to award wins including its Gold Medal Melbourne Design Award and VIVID Furniture Award in 2016, helping get its name out to its target base of mid-to-high end residential and commercial clients.

To keep growing, Cush said he is eager to keep learning about all aspects of the business and disrupt his own methods.

“It may sound counter intuitive but I consider it good practice in any industry, that once you feel too comfortable with a particular way of working to put it to one side and see if you can learn another approach,” he said.

“Worst case scenario you have your old practices to fall back on but you never know, you might just stumble upon something that revolutionises your business.”

Image: Bryan Cush. Source: Supplied.

Trending

Daily startup news and insights, delivered to your inbox.