The Australian Government is gearing up to introduce draft legislation that will force tech companies such as Facebook and Google to decrypt the content of messages sent by their users for Australian law enforcement agencies.

Prime Minister Malcolm Turnbull and Attorney General George Brandis made the announcement at a press conference in Sydney on Friday morning, with Turnbull saying, “We need to ensure that the internet is not used as a dark place for bad people to hide their criminal activities from the law.”

According to Brandis, the government will introduce legislation that will “impose an obligation” upon both device manufacturers and service providers to “provide appropriate assistance to intelligence and law enforcement on a warranted basis” in order to investigate and prosecute “serious crime”, such as counter terrorism.

It comes as acting AFP Commissioner, Michael Phelan said that 65 percent of the organisation’s serious and organised crime investigations, counterterrorism investigations, and major paedophile investigations, now involve “some sort of encryption”.

Brandis believes the new laws simply be bringing existing legislation up to date with modern technology.

“It has always been accepted that in appropriate cases, under warrant, there can be lawful surveillance of private communications,” he said.

“What we are doing, is bringing those existing legal obligations up to date. We are contemporising them. The existing law was written before the advent of social media, before the growth in very recent years of encryption of communications to a point at which it is now effectively ubiquitous. So in order to address the new technological developments, we are contemporising existing, well-established legal principles.”

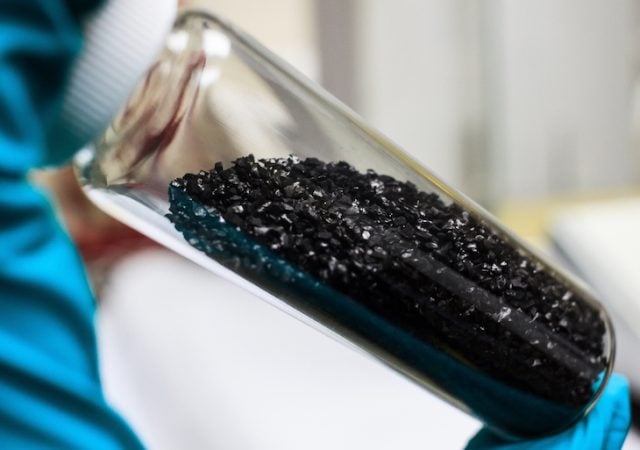

With Turnbull stating the government would not be looking to tech companies for back doors, how the government will be looking for tech companies to provide access to encrypted messages is not clear; the very nature of end-to-end encryption means only the sender and receiver have access to the keys, allowing for no access by third parties.

When questioned by a journalist as to whether the government is asking Facebook and Apple to keep a copy of the keys it gives to users, Turnbull said, “I’m not a cryptographer, but what we’re seeking to do is to secure their assistance. They have to face up to their responsibility. They can’t just wash their hands of it and say: ‘It’s got nothing to do with us’.”

The legislation will be based on similar laws in UK, with Brandis telling the ABC this morning he had been assured by a cryptographer at the UK’s Government Communications Headquarters (GCHQ) that they could crack end-to-end encryption.

Tech companies have been outspoken on their arguments for encryption.

Apple CEO Tim Cook last year told World News Tonight, “People like to frame this argument as privacy versus national security. That is overly simplistic and it is not true. This is also about public safety. The smartphone that you carry has more information about you on it than any other singular device or any other singular place.”

A spokesperson for Facebook said, “We appreciate the important work law enforcement does, and we understand their need to carry out investigations…at the same time, weakening encrypted systems for them would mean weakening it for everyone.”

Trending

Daily startup news and insights, delivered to your inbox.