Unicorn. The term has been widely adopted by international tech startup communities and is used to identify a company that has achieved a minimum of $1 billion in market capitalisation prior to any event involving liquidity like an IPO, acquisition or some other form of exit.

Although the term ‘unicorn’ is definitely used in Australia amongst particular cliques of investors and high growth startups, I would strongly argue – based on well over 2,500 interviews conducted by Startup Daily since 2012 with players in the Australian and New Zealand technology startup ecosystem – only a small portion of startups realise the importance that some venture capitalists place on unicorn companies and the role they can play in a successful startup ecosystem.

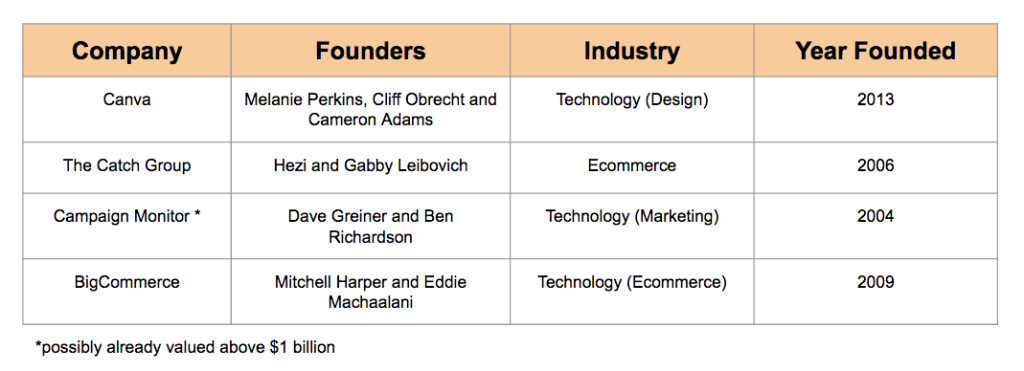

On the flip side, entrepreneurs and the wider ecosystem need to understand that the reason they are called unicorns is because they are extremely rare. Neither Google or Amazon ever reached ‘unicorn status as private companies for example. Forbes.com tracks these companies around the world on a quarterly basis; and the last published list had identified 80 companies that were eligible for ‘unicorn status’ – including Atlassian, founded by Australians Mike Cannon-Brookes and Scott Farquhar, which upon publication ranked number 20 in the world just behind other technology startups like Stripe and Spotify. According to the recently released CrossRoads Report: 2015 there is also an estimation that Sydney based Campaign Monitor has a market capitalisation of at least $1 billion. However, for now that is just an educated assumption, not a confirmed statistic.

If it were true, that would mean that right now, Australia is home to at least one and a maximum of two unicorn companies. (Remember that companies like SEEK, REA, CarSales, etc are public companies).

Unicorn companies are no longer fantasy

You can’t argue with the fact that within the last 12 months the global tech startup ecosystem has seen more companies than ever before rise to the status of unicorn. Just this week hipster glasses ecommerce play Warby Parker joined the club with its new billion dollar valuation. In fact, it’s starting to become an occurance that happens every other month with New York based marketing startup Sprinklr reaching a $1.17 billion valuation in March.

But is this rapid-growth of unicorns across the world a good thing? There are many investors in Silicon Valley, Australia and beyond that say the increase in the number of billion dollar valuations is the sign of an impending tech bubble. There are others, however, that say the valuations are entirely justified. Earlier this year in a Fortune Magazine cover story around billion dollar startups, renowned venture capitalist Marc Andreessen said that CEOs of tech companies aged 35 years or below did not go through the year 2000, which means these people – who make up a majority of the current list of unicorn companies – have not experienced the capital markets shutting off overnight, which can lead many of these founders to believe that they can always raise money at a higher valuation.

While the above is a good point, there is little value in comparing the world in the year 2000 to the world now. The connectedness of the world has changed, the internet then to the internet now is incomparable and the access to a digital world has never been higher. Not to mention, markets that were considered “third world” in the year 2000 have been rebranded as “emerging markets” and have economies that are growing at an unprecedented rate. Finally, it can be argued that many of the current startups raising large amounts of capital have the actual customer demand and market saturation and revenue to match more-so than their dot-com boom counterparts.

The other major factor that we need to be aware of is that venture capitalists know that eventually there will be some kind of market-dip. Things go in cycles; investors have been through many of them and so it makes perfect sense that in order to protect themselves and their investments, that they would encourage startups to raise more new money than is needed. It allows startups to manage their “burn-rates” more effectively and plan the money out over a longer period of time, just in case there is a future bubble-burst. At least, there will be capital to continue building the business.

The capital raises of startups like Instacart ($44 million followed by a $120 million raise six months later) are indicative of this practice. Locally, to a much lesser degree, we have seen companies like design startup Canva making similar moves with two smaller seed raises totalling to $6 million. It would hardly be surprising given the recent milestone of hitting 2 million users, that another couple of funding rounds would take place over the next 12 months pushing up Canva’s valuation and increasing its runway of capital to protect it from any future interruptions to the capital market.

Potential future Australian and New Zealand Unicorns

Whilst there are certainly a number of high-growth tech companies in Australia, it would be misleading to say that everyone has the potential to be a unicorn. Based on in-house research and data, Startup Daily has identified the following Australian or New Zealand startups as potential startups to reach unicorn status within the next five years, if they were to take on a significant amount of funding. Remember that startups like Xero are public companies so are ineligible.

If you look at the current investors in these startups there is a commonality that stands out among them – for the most part, at one stage or another, all have commented on how they get startups to explain to them why their idea is a billion dollar idea. This is much more common coming from US based investors compared to Australian ones. There is something to be said about the psychology of that process – it is no easy feat to show someone how you are going to reach a billion dollar valuation, but in my personal opinion it’s a process that could be worth adopting.

If you look at the current investors in these startups there is a commonality that stands out among them – for the most part, at one stage or another, all have commented on how they get startups to explain to them why their idea is a billion dollar idea. This is much more common coming from US based investors compared to Australian ones. There is something to be said about the psychology of that process – it is no easy feat to show someone how you are going to reach a billion dollar valuation, but in my personal opinion it’s a process that could be worth adopting.

It is worthy to note that there are perhaps even local startups that have not launched or even been created yet that could reach unicorn status in the next five years as well. Such a possibility is evidenced by startups like transport startup Uber and tech productivity play Slack.

Why do investors love Unicorns?

Money. It really is that simple. In the U.S., 90% of the returns for venture capitalists come from an average of 15 companies. It is important to note that the valuations of startups even when they reach the status of unicorn are always in constant flux – there are cases where unicorns have still made a loss for investors. Take ecommerce startup Fab, for example, founded by Jason Goldberg and Bradford Shellhammer. The company raised over $300 million in funding and at its peak had a market cap of $1.5 billion. In March this year it’s acquisition by PCH International was everything but fab, selling at a reported $15 million or 1% of its former value according to a report by Bloomberg.

Overall, this strategy of backing unicorns has enabled venture capital firms to become billion dollar operations themselves, replenishing their funds and allowing them to continue investing in the next generation of potential startup unicorns.

But what about the startups that are not destined to be unicorns but are still strong, profitable, multimillion dollar ideas?

According to Micah Rosenbloom, a venture partner at Founder Collective, these companies are called thoroughbreds. In an op-ed for Techcrunch last year, he explained thoroughbred companies as “impressive [organisations] that have the potential to change the lives of their customers and employees, but differ from unicorns in that they are ‘only’ likely to exit for $100-500 million dollars”.

Should we be obsessed with becoming a Unicorn company?

The short answer is no. Australia and New Zealand’s startup ecosystems still have too many issues that need to be solved at a macro-level to become obsessed with worrying about valuations. The first hurdle we need to tackle is getting more startup entrepreneurs to think globally from the beginning. And I mean thinking globally from a strategic perspective. At least 50% of local startups that we have reported on in the last two years have been copy-cat companies that already have major competitors in the U.S., Asia or Europe.

For the most part, companies that have reached unicorn status have been the first sustainable model of their idea to go to market or have been able to obliterate a market leader with a killer unique point of difference to its competitor. Australian companies like Atlassian, Campaign Monitor and Canva are all very clear examples of what I am talking about here – Australian startups with global appeal and support systems.

In order to get the capital flowing a little more freely across the nation and into the startup ecosystem, Australia and New Zealand need to become expert at being able to produce successful thoroughbred companies first. If we don’t do that, then we will never attract the level of both local and international investment we need to keep local startups in country and attract expat founders to our region.

Trending

Daily startup news and insights, delivered to your inbox.